16 December 2010

14 December 2010

Wishing Stairs - Black Swan

Seeing the trailers for Black Swan reminded me the Korean horror film Wishing Stairs from a few years back. I think it's available on Netflix streaming right now. The movie has a long, atmospheric setup, and, in the tradition of many Asian horror films, gets a little confusing near the end, but it is not too bad for the genre.

The beginning of the trailer below will show you a few of the similarities. (In Wishing Stairs, Giselle is the central ballet.)

The beginning of the trailer below will show you a few of the similarities. (In Wishing Stairs, Giselle is the central ballet.)

01 December 2010

Movie Posters - Holiday Edition - Planes, Trains and Automobiles

These two comic icons were also great comic archetypes - as well as a American socio-economic types. The use of white space is just about perfect. Notice how Mr. Martin crowds slightly out of the border on the left side?

And the angle brings your eye down to the literal and symbolic baggage that Candy's character tugs along with him throughout the film.

30 November 2010

Movie Shot of the Week - Oh, God! (1977)

How, in a comedy, do you make the physical entrance of God memorable? Set it in the bathroom, and use mirrors to multiply the anticipated effect of our first seeing the film's big star, George Burns.

There is post work in the shot, so it isn't really pure. The bottles on the sink to the left give it away.

18 November 2010

Kairo - and The "Pulse" of Loneliness

I was reading Roger Ebert's recent entries on his blog. He talks about loneliness, and a little about its relationship to social media or the Web.

What do lonely people desire? Companionship. Love. Recognition. Entertainment. Camaraderie. Distraction.

Encouragement. Change. Feedback. Someone once said the fundamental reason we get married is because have a universal human need for a witness. All of these are possibilities. But what all lonely people share is a desire not to be -- or at least not to feel -- alone.

You are there in the interstices of the web. I sense you. I know some of you. I have read more than 78,000 comments on this blog, and many of them have been from you. I know two readers who if possible would never leave their homes. I know more who cannot easily leave, because of illness or responsibilities. I don't know of any agoraphobics, but there probably are some. Just because you're afraid to go outside doesn't mean you're happy being inside.

I couldn't help thinking of Japanese filmmaker Kiroyishi Kurosawa's 2001 ghost film Kairo. The film's title has been translated to "Pulse" and the movie was remade into a relatively respectful, but ultimately unremarkable American film of that title.

Kairo is a somewhat complex film and is a little difficult to get a handle on with a first viewing, and the pace is almost too slow. But there is an undeniable artistry in Kurosawa's vision of the near future. A short summary of the "plot" makes it sound ridiculous. It is not.

The main idea of the film is that ghosts have found a way to bridge into this world through the internet. Apparently heaven is full and the ghosts figure that if they can keep people from entering the equilibrium will maintain. How the ghosts achieve this is one of the film's unexplained mysteries, but essentially the ghosts' victims sort of fade away and become large black stains on the wall that eventually disappear.

While the encounters with the ghosts are chilling, I will always remember the small moments of the film where suddenly the camera angle switches to the POV of the victims, still conscious inside an isolated existence. All the noise on the soundtrack cuts out as we hear the pitiful pleas that will never be heard: "Help me. Help me. Help me."

As the movie continues, the city becomes desolate as the remaining characters ride empty subway cars and drive through empty streets where every darkened corner appears to spread slowly across the screen, threatening to engulf them. A hopelessness and dread is woven into every second and every shot. This journey through lonely Tokyo contains the film's only nod towards the conventions of the large-scale apocalyptic epic - a military cargo plane drifts overhead slowly, flying way too low, crashing somewhere over the horizon. And even this effect is somewhat muted and quiet.

Indeed, the overall effect throughout is that of the world slowly disappearing, giving itself over to the impending void while the survivors hang on to the last threads of human connection, however slight they may be.

17 November 2010

26 October 2010

Paranormal Activity - More of the Same - But That's O.K.

Paranormal Activity 2 is a rare kind of sequel. It is exactly as good as its predecessor. However, this means that while it is no worse, it is also no better.

Well, let me revise that. There is a little tedium that sets in with the second installment because the concept doesn't feel as fresh. They have a found a way to multiply the passive camera effect, but, unfortunately, more angles only produce more of the same after a while.

Some things I found interesting about the writing: (Slight spoilers.)

1. The franchise still hasn't established any sort of clear story rules. We know that this is a demon, but what are its powers? Its operating procedures are very hazy - sometimes it leaves footprints, but other times it seems to float as a vapor?

2. The "prequel" structure of the second movie sets up a third act that may be very difficult for audience members to completely follow if they haven't seen the first movie. Although this could be deliberate - making a kind of interlocking series of stories that rotate around each other.

3. Like the first movie, the characters in the second movie do things that just simply don't make sense. For instance, in this movie, it is weird when one character at a certain point doesn't simply go to a neighbor's house. (Those who have seen the movie will understand.)

Paranormal Activity 2 provides several really good jumps, some minor scares and some very suspenseful moments, but beyond that it is not much. However, if you are looking for that, you pretty much can't go wrong, which may be its appeal.

Many critics are straining to make something out of the upper middle class "mcmansion" setting of both films, but after the second one, I am almost convinced the filmmakers have no real interest in that idea.

27 September 2010

Get a Prorated Ticket for the First Five Minutes of Devil...

The opening title sequence of Devil, a new horror film "from the mind of M. Night Shyamalan" is fantastic.

The camera soars over the suspension bridges and skyscrapers of Philadelphia, but the simple act flipping the picture upside down works beautifully to achieve just the right mixture of unease, tension and, well, fun that the movie needs.

However, the rest of the film, I'm sorry to report, just keeps going downhill from there. This movie was not screened for critics, but it is not nearly bad enough to warrant that particular move by the studio - that's usually reserved for real turkeys.

Below, the trailer gives you a taste of those opening visuals, but seeing it on a big movie screen is more impressive, or at least it was for me. Save your money though.

Labels:

Horror,

Shyamalan,

The House of the Devil,

Title Sequences

26 August 2010

What do filmmakers do at lunch anyway?

The director and I work out an upcoming shoot for our short film.

19 August 2010

Jaws on the Big Screen

Just got back from seeing Jaws on the big screen at the Somerville Theatre. It is playing tomorrow night as well.

As you can see from the promotion above, there was plenty of good fun had by all. And I can report that Jaws still can make 'em jump!

14 August 2010

Columns and Temples In Kubrick's Full Metal Jacket

Stanley Kubrick's Full Metal Jacket is often critiqued as being two different movies. The first half is a spartan portrayal of Marine boot camp that ends with a bloody look into to the face of madness. The second half brings several of the players from that fascinating basic training sequence into actual fighting in the cities of Vietnam. The second half climaxes in an assault on a building in which a sniper is pinning down and picking off Marines.

However, there is so much symmetry connecting the first half and the second that it is really hard to separate them.

I thought I would just show one of the image motifs Kubrick enforces in the first half of the film, only to spring it on us in the climax of the second.

There is, of course, the above image which, with the recruits in their white underwear and t-shirts, emphasizes the orderliness of basic training. The exception to the rigor of the shot above is the jelly donut being eaten by Private Pyle, along with the scattered contents of his footlocker - it almost makes literal Pyle's inability to "keep his shit together."

As you will see below, the columns of the barracks are ever present, framing everything confining the viewer and perhaps comforting the recruits?

In the shot below, Private Joker(Matthew Modine)approaches the mouth of madness on the platoon's last night in their Parris Island barracks. Lit in moonlight blue, the shot heralds the lunacy that awaits him at the end of the columns.

Now, at the end of the second half of the movie, Modine has entered a building and ascended to the top floor where a sniper is known to be hiding. (Remember that during boot camp, the drill instructor praises the marksmanship of Lee Harvey Oswald to the recruits.)

Does anything about the temple-like room below look familiar? There are the columns, awaiting Joker's final approach to the altar, only the orderliness has been been transformed into a vision of hell.

Note how the gating on the left side of the shot somewhat mirrors the steel bunks lining either side of the barracks from the earlier shots.

Two Sides of the Same Cinematic Coin

For a 1996 live interview on Terry Gross's Fresh Air, Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert were each asked to bring a scene from a film.

Ebert began the interview by saying that he was going to bring the famous clip from The Third Man with the cat in the doorway. However, upon revealing this to Gene Siskel, he was wisely reminded that the interview was for radio and The Third Man scene has no words.

Ebert changed his selection to a great monologue from Citizen Kane, and, in turn, this inspired Siskel to bring an almost reactionary scene from a film that was current to the time the interview was being taped.

Here are both those scenes. Watch the Citizen Kane clip, then the one after.

Ebert began the interview by saying that he was going to bring the famous clip from The Third Man with the cat in the doorway. However, upon revealing this to Gene Siskel, he was wisely reminded that the interview was for radio and The Third Man scene has no words.

Ebert changed his selection to a great monologue from Citizen Kane, and, in turn, this inspired Siskel to bring an almost reactionary scene from a film that was current to the time the interview was being taped.

Here are both those scenes. Watch the Citizen Kane clip, then the one after.

14 July 2010

13 July 2010

Book Review - D.W. Griffith; An American Life

If you are looking for a place to start learning about D.W. Griffith, the early silent film director who is known for having revolutionized cinema when it was still in its infancy, you may want to start with Richard Schickel's huge biography of this cultural legend.

D.W. Griffith; An American Life, was originally published in 1984 to wide acclaim and it has remained in print. While books have been written about specific periods in his creative and public life, such a large scale attempt at Griffith's life has not, to my knowledge, been repeated.

His name is forever linked, of course, to the infamous The Birth of a Nation, a landmark film that brought cinema into another realm and really put the United States at the vanguard of a new art form for decades to come. That Nation was also an insidious piece of racism is a dichotomy that still causes trouble for critics and film buffs.

Griffith’s early days at the Biograph Studio were filled with experimentation and, most importantly a sense of ensemble. He worked as an actor in Biograph’s early films, the first being a short film where he rescues a baby trapped in an eagle’s nest. After a time, he found his way into the director’s chair, and suddenly his ambition and natural artistic talents, (which up until that point had not found him success in the traditional theater,) were meeting a growing medium that required what he had to offer.

Schickel’s book was originally published in the early 1980’s, at a time when most of the films he discusses and analyzes, especially those one-reelers from the Biograph years, would have been unavailable for general viewing. Now, many of these films are readily available on DVD or free on the Internet – some are in the public domain. Reading the book now allows a reader to experience most of the important films Schickel describes, and neither Schickel’s analysis or Griffiths films are any lesser for it.

Many of the technical innovations that are credited to D.W. Griffith are now known to be the contributions of the skilled camera operators and lens makers that populated the field during that time. Schickel explains that Griffith should be credited some of the artistic revolution of cinema at the time than with the actual mechanical innovations. Sometimes these were the result of a cooperation of sorts.

Shickel builds all of this early groundwork to prepare us for the most controversial, famous and artistic high points of Griffith’s life: The Birth of a Nation and Intolerance. Taken as one-two punch, (the two films were not released THAT far apart,) it is almost impossible to think of a

Like the Biograph years, Griffith’s years of making films after Birth and Intolerance are laid out just as meticulously. And they give an excellent understanding of Griffith’s place in the movie world as it approached the sound era. He was, really, the first star director – he was the only director that was a principle in the formation of United Artists.

Ironically, it was Griffith’s failure to anticipate or capitalize on the star system that probably plagued him more than any of his oversights. The practice of keeping a very close cadre of personnel on a very short leash helped Griffith maintain dictatorial control of his projects, but also resulted in casting, (especially among his male actors,) that still leaves critics and historians scratching their heads. As bankable stars made money for themselves and studios, Griffith’s films languished in a kind of strange critical and box office no man’s

Ironically, it was Griffith’s failure to anticipate or capitalize on the star system that probably plagued him more than any of his oversights. The practice of keeping a very close cadre of personnel on a very short leash helped Griffith maintain dictatorial control of his projects, but also resulted in casting, (especially among his male actors,) that still leaves critics and historians scratching their heads. As bankable stars made money for themselves and studios, Griffith’s films languished in a kind of strange critical and box office no man’s

His name is forever linked, of course, to the infamous The Birth of a Nation, a landmark film that brought cinema into another realm and really put the United States at the vanguard of a new art form for decades to come. That Nation was also an insidious piece of racism is a dichotomy that still causes trouble for critics and film buffs.

When the American Film Institute released its 100 Greatest American Movies list in June 1997, The Birth of a Nation sat right there at number 44. However, ten years later, the list was released again and The Birth of a Nation had dropped off the list altogether; it seemed it was literally replaced by Intolerance, another Griffith film which had not appeared on the earlier list.

Schickel brings to life the whole electrifying period surrounding the making, release and reception of The Birth of A Nation. His details are illuminating and go a long way towards clarifying misconceptions or reinforcing what we already know.

Schickel brings to life the whole electrifying period surrounding the making, release and reception of The Birth of A Nation. His details are illuminating and go a long way towards clarifying misconceptions or reinforcing what we already know.

However, the rest of the book is simultaneously frustrating and exhilirating. Schickel brings us

along for the early part of Griffith's life - his boyhood growing up in the South of the post Civil War Reconstruction and his forays onto to the legit stage. He sought fame as an actor and even took a few tries at playwriting, never quite finding his niche.

The invention of film was his saviour, even though he couldn't see it clearly at first - in his early

days of acting in and directing silent one-reelers he still went under a pseudonym of sorts. And these passages are truly engaging. Schickel brings to vivid life the landscape of early motion pictures, complete with its lawsuits, business practices and egos. It is an exciting time that is imbued, through meticulous research and writing, with all the wonder, anxiety and trepidation that must have existed.

Griffith’s early days at the Biograph Studio were filled with experimentation and, most importantly a sense of ensemble. He worked as an actor in Biograph’s early films, the first being a short film where he rescues a baby trapped in an eagle’s nest. After a time, he found his way into the director’s chair, and suddenly his ambition and natural artistic talents, (which up until that point had not found him success in the traditional theater,) were meeting a growing medium that required what he had to offer.

Schickel’s book was originally published in the early 1980’s, at a time when most of the films he discusses and analyzes, especially those one-reelers from the Biograph years, would have been unavailable for general viewing. Now, many of these films are readily available on DVD or free on the Internet – some are in the public domain. Reading the book now allows a reader to experience most of the important films Schickel describes, and neither Schickel’s analysis or Griffiths films are any lesser for it.

Many of the technical innovations that are credited to D.W. Griffith are now known to be the contributions of the skilled camera operators and lens makers that populated the field during that time. Schickel explains that Griffith should be credited some of the artistic revolution of cinema at the time than with the actual mechanical innovations. Sometimes these were the result of a cooperation of sorts.

Shickel builds all of this early groundwork to prepare us for the most controversial, famous and artistic high points of Griffith’s life: The Birth of a Nation and Intolerance. Taken as one-two punch, (the two films were not released THAT far apart,) it is almost impossible to think of a

similar groundbreaking accomplishment by ANY director since. (Think, maybe, James Cameron releasing Titanic and then, two years later, Avatar.)

While doing his best to keep things in perspective, Schickel deploys superlatives when the situation calls for it. For instance, the box office success of The Birth of Nation remains pretty astounding for any time, even as Schickel does his best to dispense with accepted legend and focus on what the research really bears out.

Also, Schickel dispels the sort of accepted wisdom that has grown up around Intolerance, a massive extravaganza that weaved together four story lines from different eras in history. Apparently, it was not made as a reaction to or an apology for the racist charges of The Birth of a Nation. Nor was it a box office disaster. Indeed, Schickel impresses that a key to understanding Griffith’s ever- descending star is that his post-Birth movies rarely were box office disasters, but rather disappointments that lost some money or simply did not make enough profit. The problem, one of many, Griffith started having was that his own finances were inextricably wrapped up into the budgets of these films – making his own attempts at starting a production company ever precarious.

Like the Biograph years, Griffith’s years of making films after Birth and Intolerance are laid out just as meticulously. And they give an excellent understanding of Griffith’s place in the movie world as it approached the sound era. He was, really, the first star director – he was the only director that was a principle in the formation of United Artists.

Ironically, it was Griffith’s failure to anticipate or capitalize on the star system that probably plagued him more than any of his oversights. The practice of keeping a very close cadre of personnel on a very short leash helped Griffith maintain dictatorial control of his projects, but also resulted in casting, (especially among his male actors,) that still leaves critics and historians scratching their heads. As bankable stars made money for themselves and studios, Griffith’s films languished in a kind of strange critical and box office no man’s

Ironically, it was Griffith’s failure to anticipate or capitalize on the star system that probably plagued him more than any of his oversights. The practice of keeping a very close cadre of personnel on a very short leash helped Griffith maintain dictatorial control of his projects, but also resulted in casting, (especially among his male actors,) that still leaves critics and historians scratching their heads. As bankable stars made money for themselves and studios, Griffith’s films languished in a kind of strange critical and box office no man’s

land – neither too successful, nor too poorly received. And when he did rise the occasion for his other masterpiece, Broken Blossoms, (left) he appeared unable or unwilling to see that he had broken some new ground again, and so he reverted back to what he knew. Although this did result in another success in Way Down East. Although, Schickel observes, Griffith's audience was never really the elite critical and taste-making society of New York City, but rather the "heartland" audience.

What Schickel reveals early on in this volume, is that the notes Griffith left behind for a possible memoir are easily proven inaccurate in some cases, or almost willfully misleading in others. To add to that, Griffith’s close knit ensemble didn’t really have a lot of ill to speak of him. Lillian Gish, an actress who worked with him extensively, wrote a biography that paints Griffith in a suspiciously flattering light.

So in his efforts to stick to what he can verify, Schickel just about surrenders the more extensive psychological profile that generally accompanies works about artists. The reader won’t find much about Griffith’s off-camera relationships with young, (sometimes too young) starlets. In fact, for long stretches, Schickel’s outline of the great director sometimes stuck me as an almost monastic portrait - consumed by work, long hours at the studio, and off nights seeing what sort of work his competitors were doing. However, we then read about hints of inappropriate affections, and we get a snippet of a letter Griffith sent to his first wife before their divorce in which Griffith hints that there have been many adulterous affairs. The images don't square.

So in his efforts to stick to what he can verify, Schickel just about surrenders the more extensive psychological profile that generally accompanies works about artists. The reader won’t find much about Griffith’s off-camera relationships with young, (sometimes too young) starlets. In fact, for long stretches, Schickel’s outline of the great director sometimes stuck me as an almost monastic portrait - consumed by work, long hours at the studio, and off nights seeing what sort of work his competitors were doing. However, we then read about hints of inappropriate affections, and we get a snippet of a letter Griffith sent to his first wife before their divorce in which Griffith hints that there have been many adulterous affairs. The images don't square.

But what of the racism in Birth of Nation and the traces of it in some of his other films? A biography of Griffith needs to deal with this, and Schickel does, relating to us a very late in life interview in which the director reveals just how deep racism may corrupt the makeup of a human being.

06 July 2010

Movie Shot of the Week - Jaws (1975)

29 June 2010

Review - House of the Devil

With only a few ironic gestures, writer/director Ti West has created a faithful and fun tribute to a certain era of horror suspense movies, at least for the first half. The House of Devil is an indie marvel in some respects - a genre film adhering to almost every rule in the book, but one that has a little life in its creaky, weathered frame. Like a veteran of late 1970's horror pictures, West shows a workman-like craftsmanship that unfortunately gets the better of him and his characters.

With only a few ironic gestures, writer/director Ti West has created a faithful and fun tribute to a certain era of horror suspense movies, at least for the first half. The House of Devil is an indie marvel in some respects - a genre film adhering to almost every rule in the book, but one that has a little life in its creaky, weathered frame. Like a veteran of late 1970's horror pictures, West shows a workman-like craftsmanship that unfortunately gets the better of him and his characters.Using minimal exposition, the film establishes an ordinary heroine with ordinary problems. Samantha, a college student suffering from Terrible Roommate Syndrome, has found the perfect off-campus apartment, but she needs to come up with the first month's rent in just a few days.

Pensively striding through the brisk autumn air, she starts looking for fast money by way of the flyers posted on cork boards around the sparsely populated university grounds. The picture is costumed and designed to fit somewhere in the decade between 1975 and 1985, but not in an overly conspicuous way. As much fun as it is to see actresses in their feathered hair, using enormous tape players and headphones, nothing screams out with quotation marks or exclamation points. Rather, the ambiguous feel of time and place works to slow the pace down enough to make the sudden ring of a lonely pay phone startle you. (There's no mobile calling in this town.)

A tear-off flyer advertises a babysitting gig that could be just lucrative enough, but there are also enough red flags to worry Samantha's best friend (Greta Gerwig) who agrees to drive her out to the Ulman house to meet the prospective employers. (The gig is naturally located in an isolated lot adjacent to the cemetery .) The deal is simple. If things are too weird with the arrangement, Samantha will abort the plan and they will leave.

25 June 2010

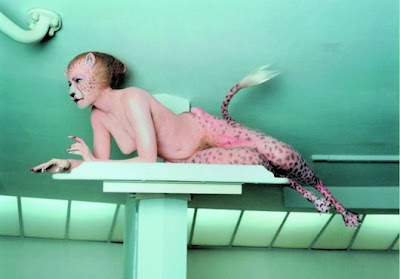

Cougar or Cremaster?

It called to mind an image or two from the trailer of artist Matthew Barney's Cremaster Cycle. Specifically this one:

The Cremaster Cycle plays in full for the next few weeks at the Kendall Square Cinema here in Cambridge as well as other cinemas across the country.

Below is a trailer for the re-release:

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)